Everything comes from somewhere. All of our world-changing inventions and revolutionary ideas. We know the stories about how the world we’ve created came to be. But some amazing stories are widely unknown. Even though they are hiding in plain sight.

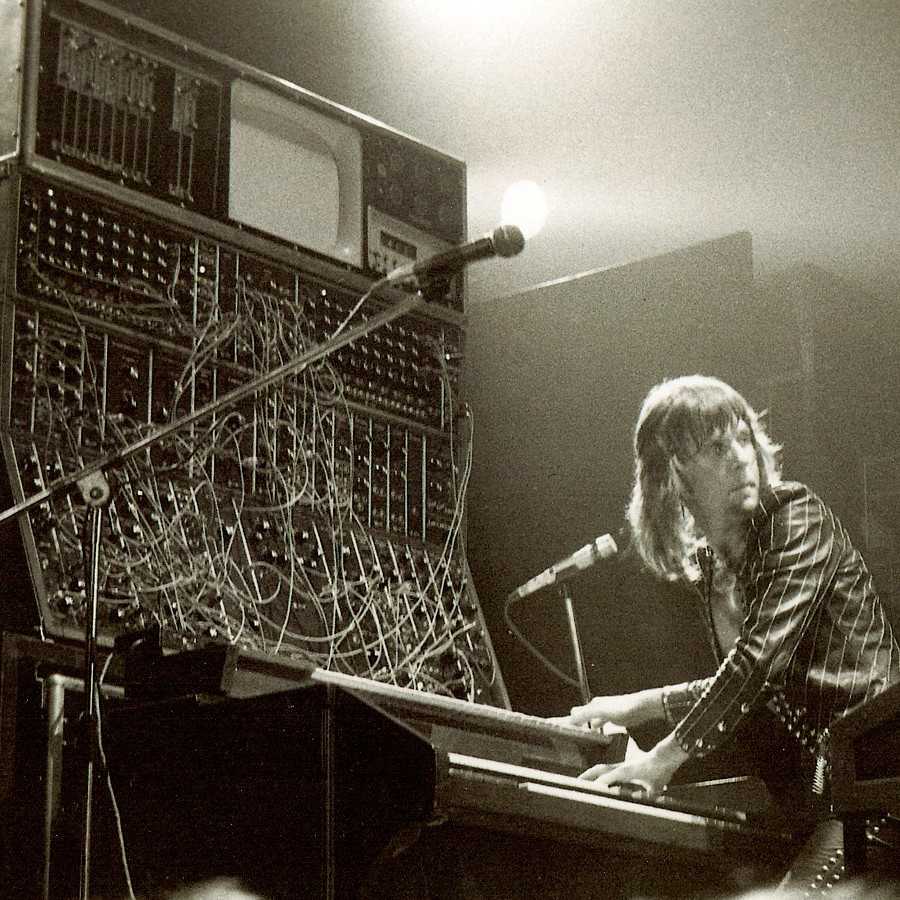

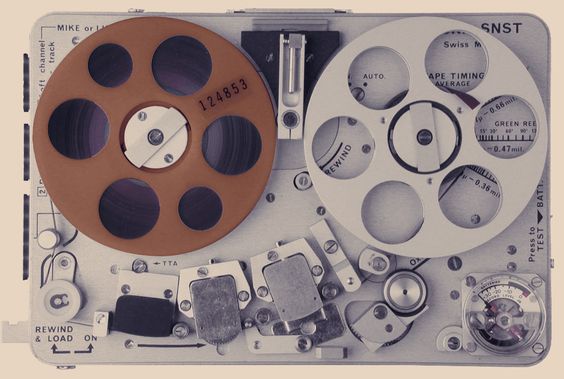

Over the past 130 years, electronic music has crept steadily from a peripherial curiosity to the default method of composing, recording, and performing popular music.

And the concept of streaming music is replacing the relevance of radio broadcasts and personal collections of recordings.

Everybody knows about the inventions of radio, the telephone, the phonograph.

But where did streaming and electronic music come from?

As impossible as it sounds, the world's first electronic streaming music service launched in 1906. And it carried the music of the world's first synthesizer, Thaddeus Cahill's Telharmonium.

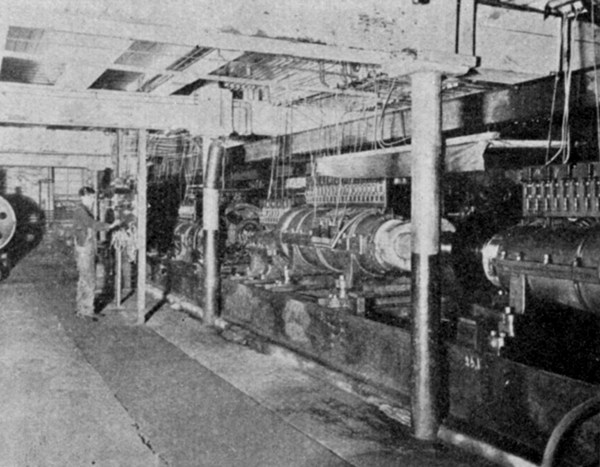

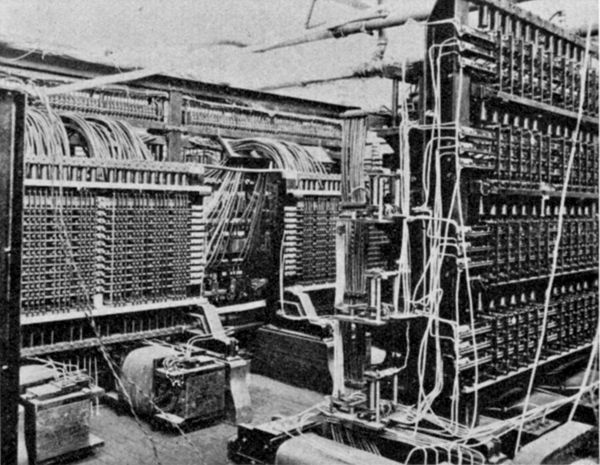

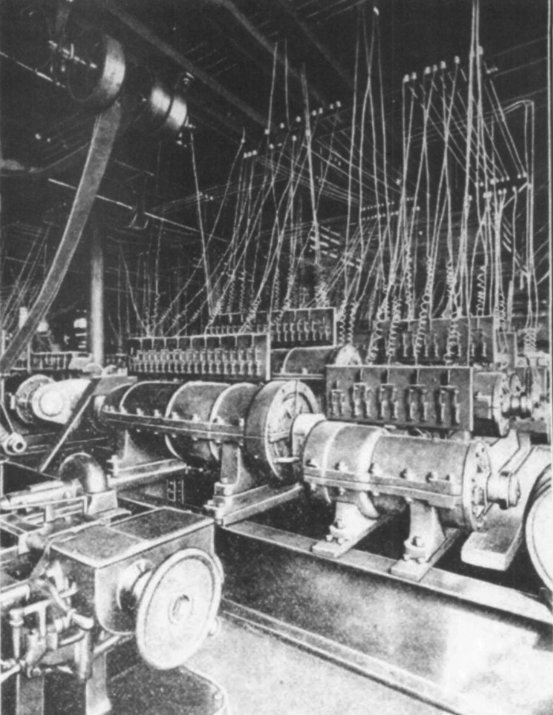

Cahill's ambitious brainchild was a 200-ton electromechanical leviathan the size of a power plant. Its dozens of massive dynamos generated one and a half million watts of musical electricity.

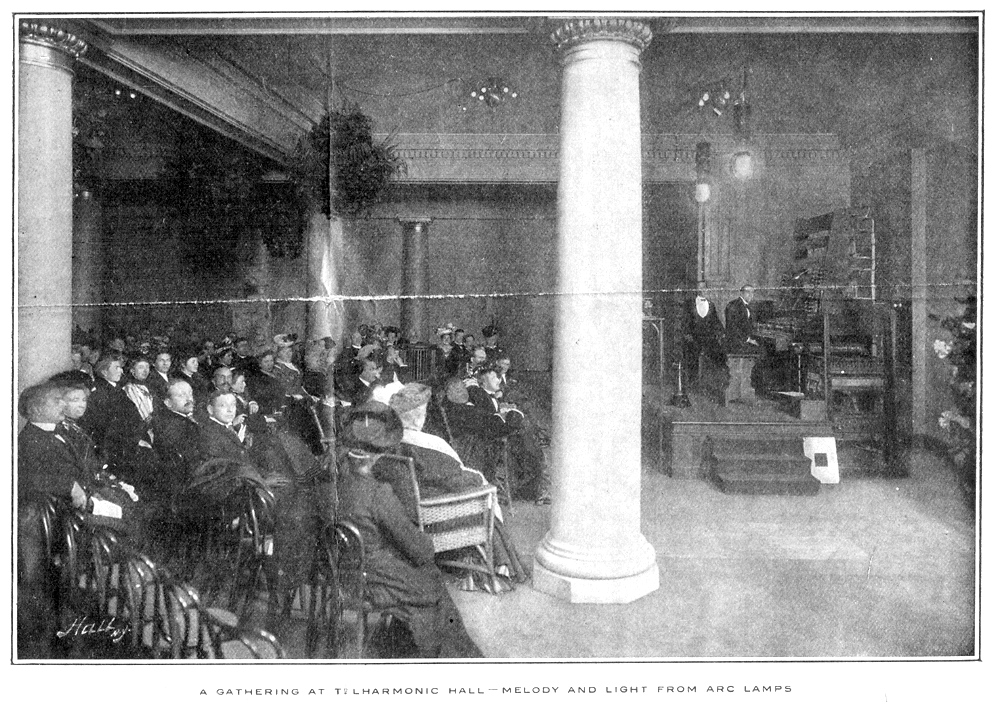

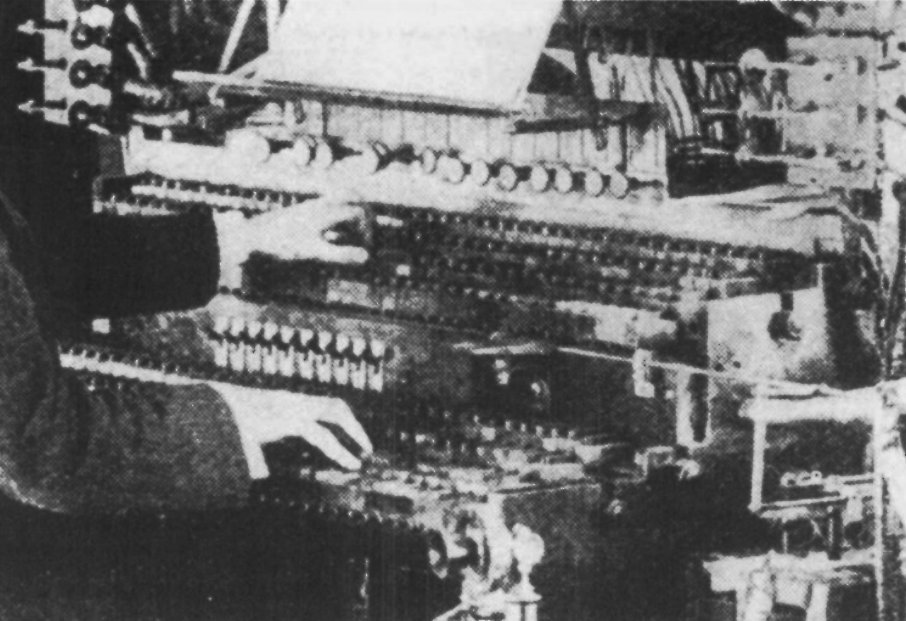

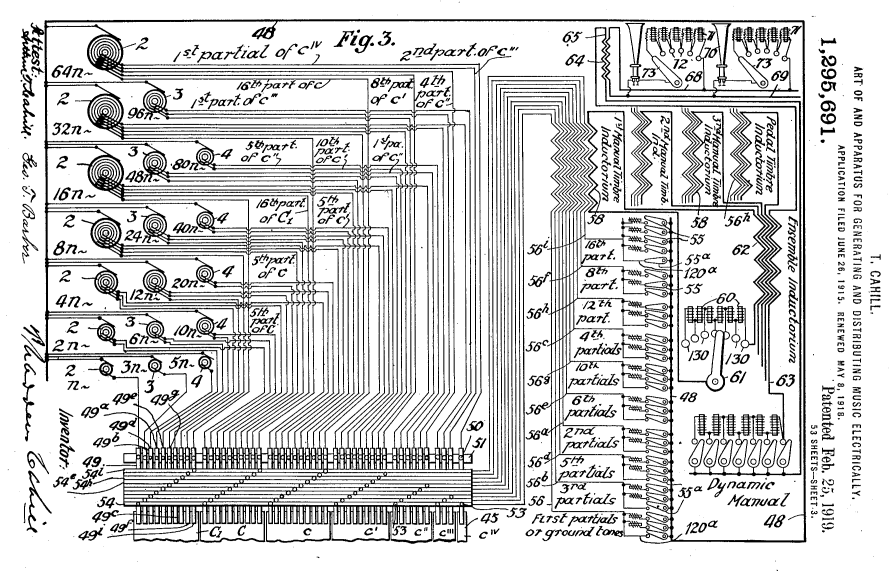

Day and night, two musicians played musical selections on the Telharmonium's two complex Dynamophone keyboards. These keys and switches and pedals would trigger, flavor, and mix the 144 channels of musical electricity and send it out over the phone lines. Any subscriber could ask their telephone operator to connect them to the Telharmonium. And the futuristic music played by the two faraway performers would come streaming over the line.

The service had thousands of subscribers in New York City — including most major hotels and restaurants. And also some private subscribers like Mark Twain, who described it in breathless terms.

“The trouble about these beautiful, novel things is that they interfere so with one’s arrangements. Every time I see or hear a new wonder like this I have to postpone my death right off. I couldn’t possibly leave the world until I have heard this again and again.”

— Mark Twain

Despite its gargantuan size, its many diverse voices were delicately expressive. One reporter was awed at how the instrument …

“… with absolute faithfulness produces the sound of bows on the strings, the clear bell tones of the brass instruments and the marvellous harmony of perfect orchestration, or the rare tones of an organ.”

There is a reason that we don't tell the story of the Telharmonium. And it's a tragedy.

Almost everything about it is lost in the mists of time. The last Telharmonium, the Mark III, stopped operating in 1916. Every last piece of it was sold for scrap in the 1950s. And there are no recordings of it. So no living person has heard the unusual music of the Telharmonium, the primodial musical beast that is the direct ancestor to all electronic music today.

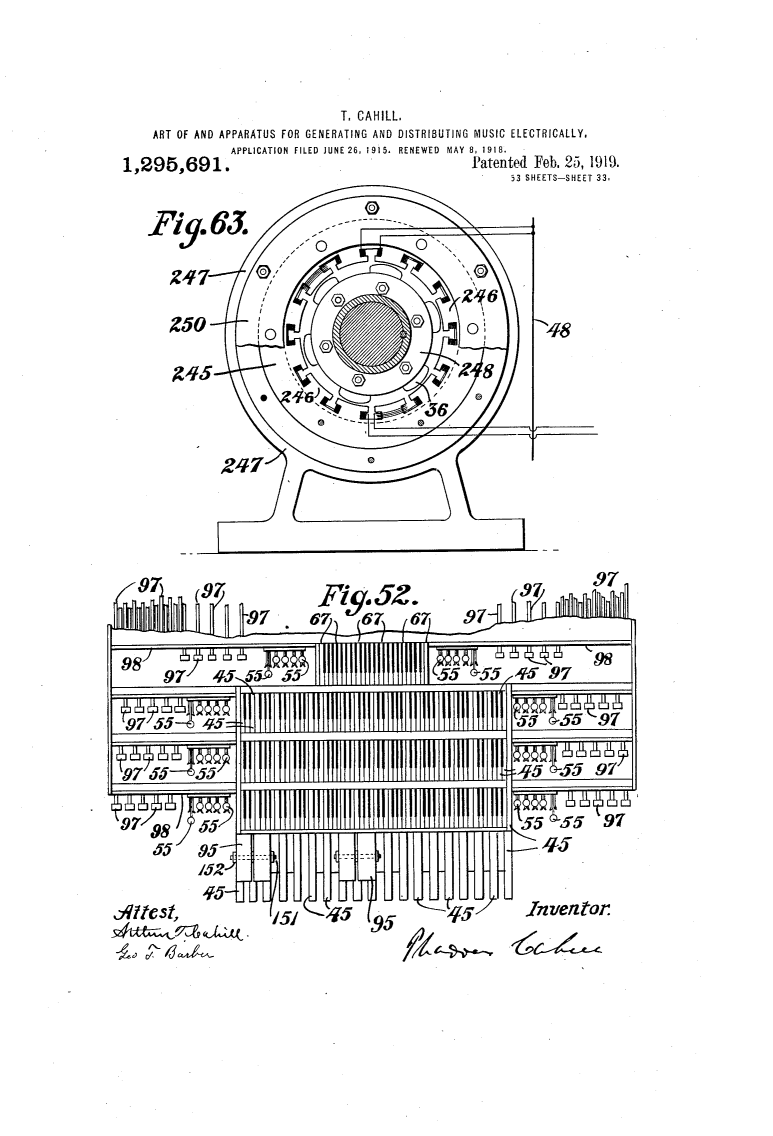

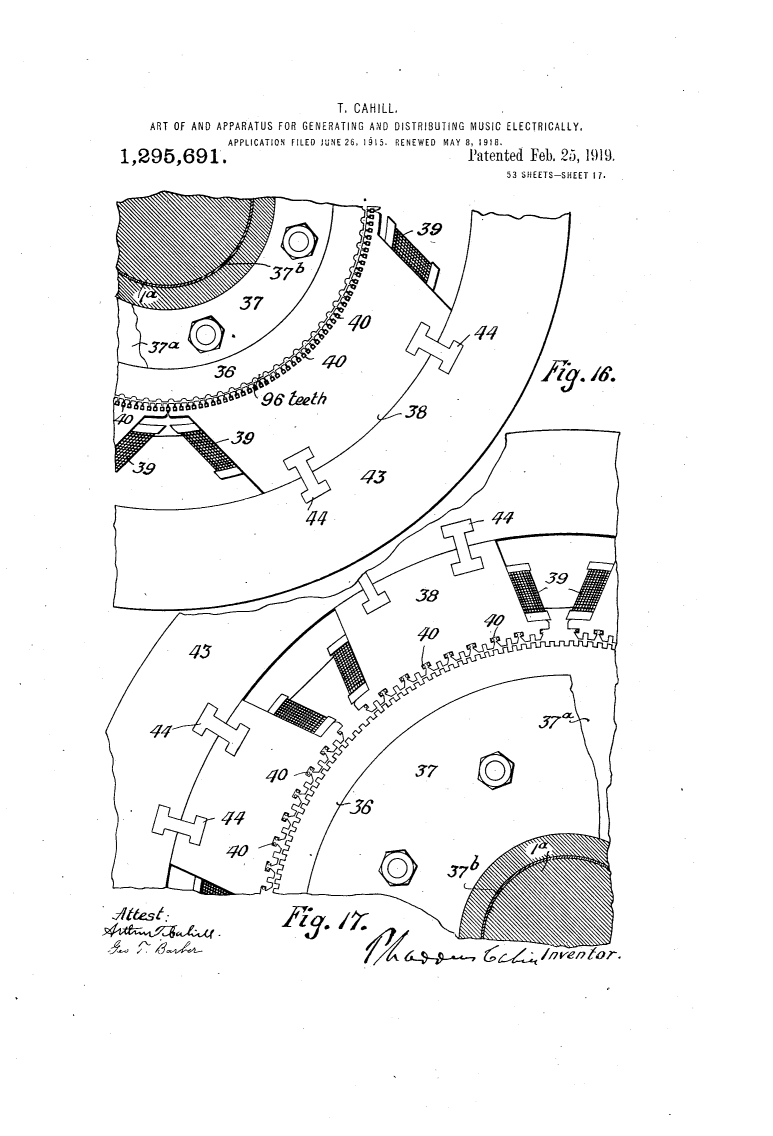

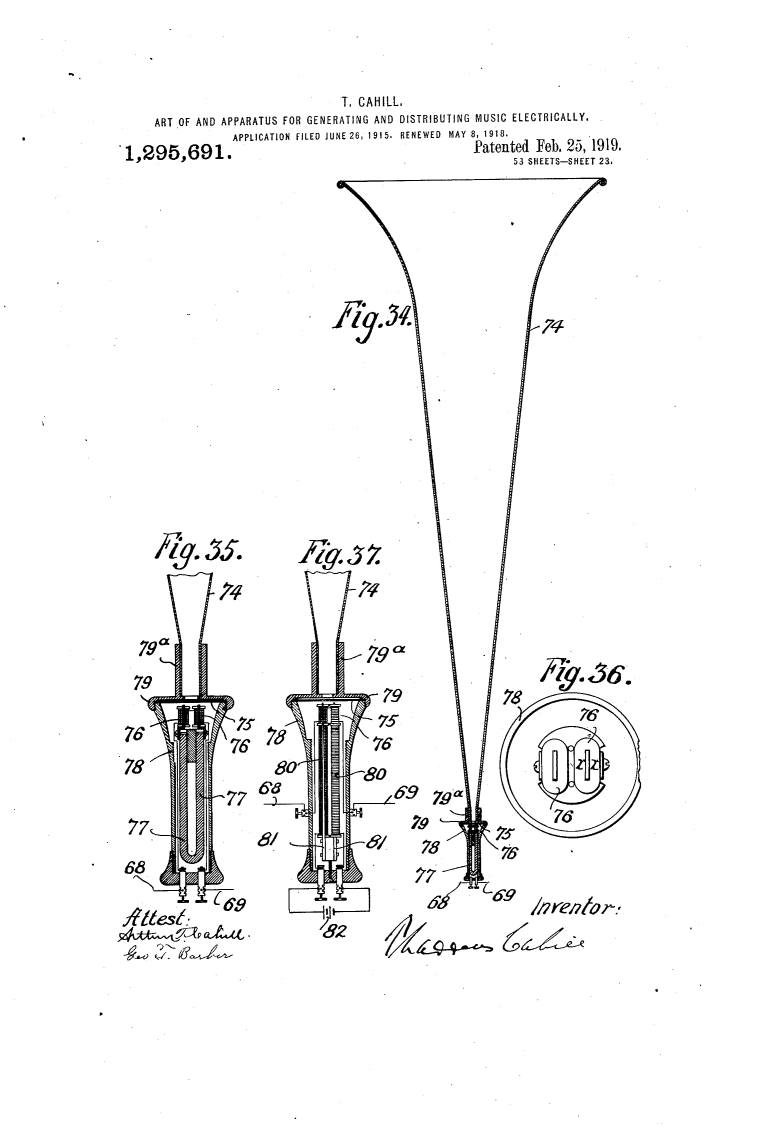

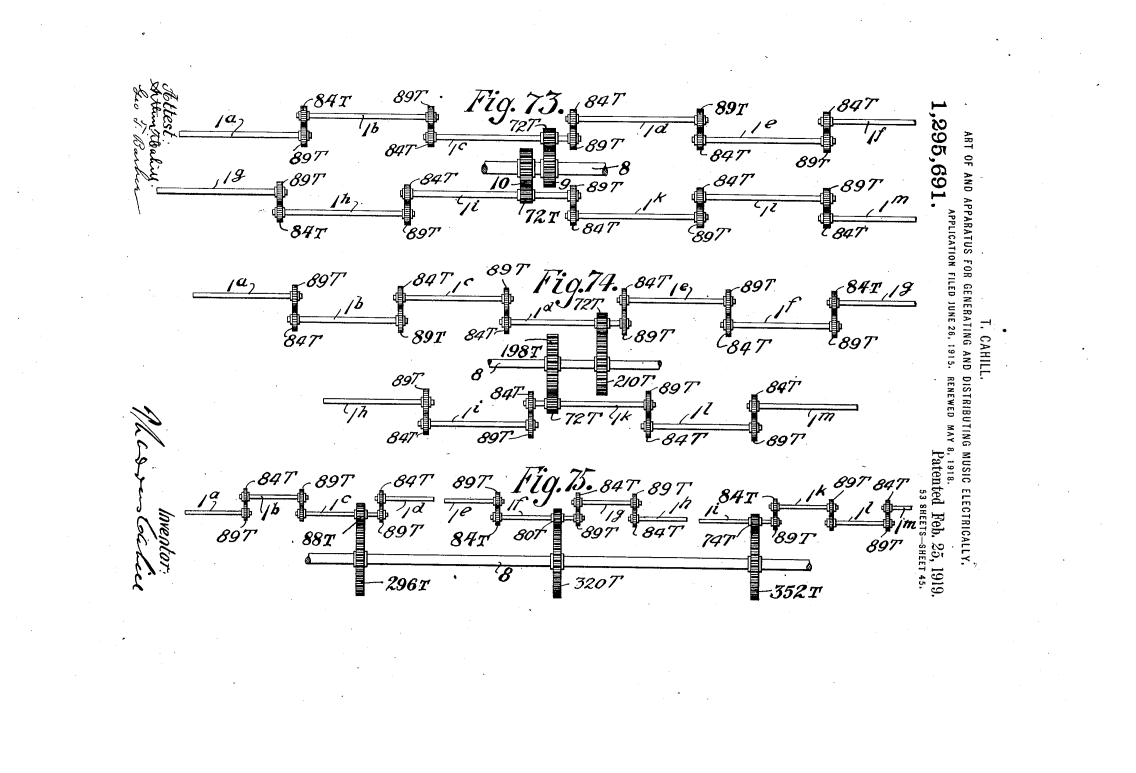

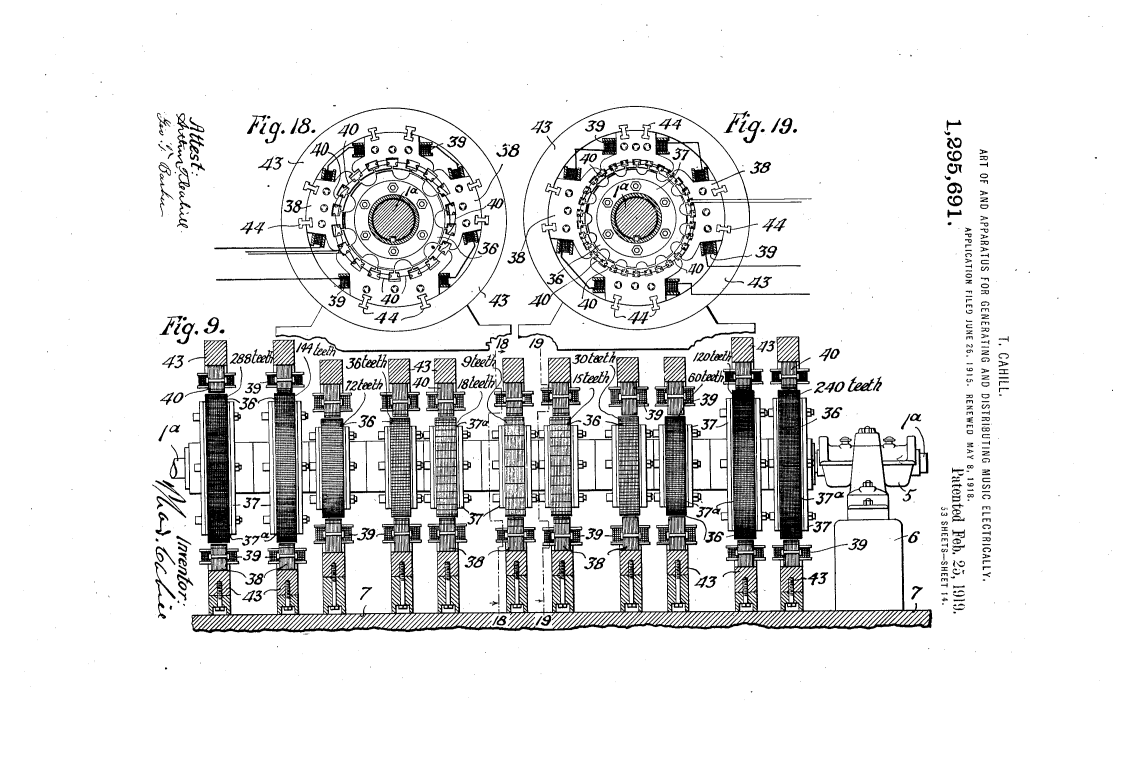

But this story isn't over yet. Much like in Jurassic Park, this musical dinosaur can be resurrected. Thaddeus Cahill left behind detailed and beautifully illustrated patents.

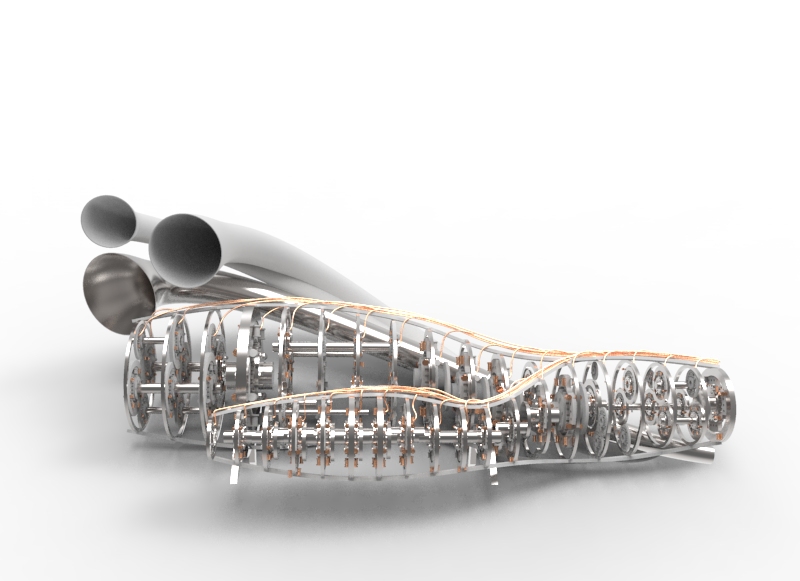

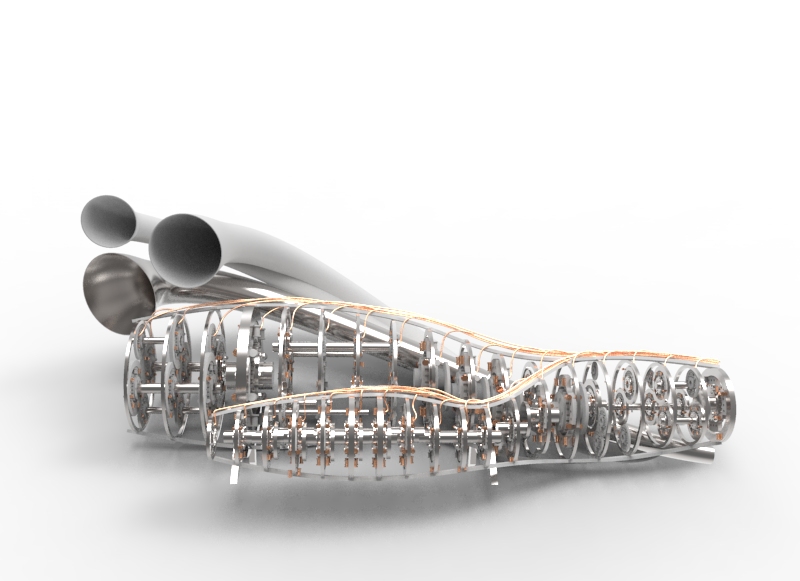

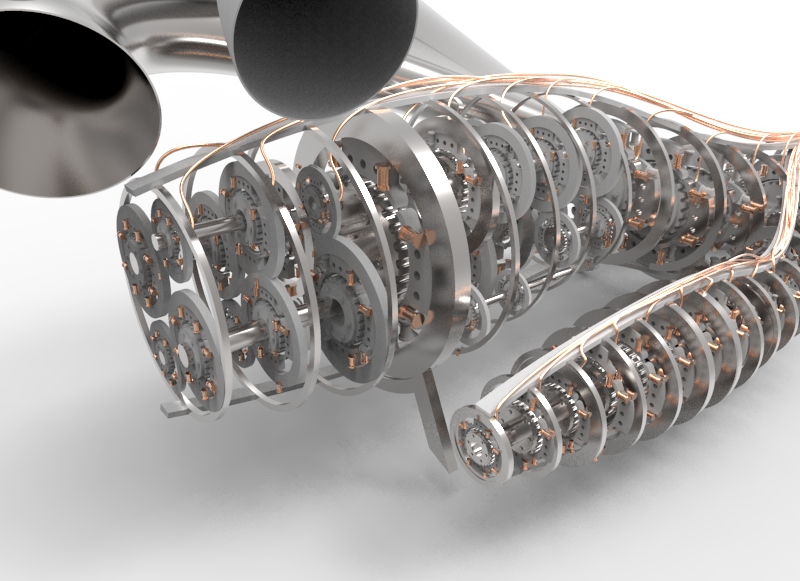

The Mark IV will be a new Telharmonium that embodies Cahill's visionary ideas and brings the sounds of his invention back to life after over a century. The massive iron tone wheels, exotic keyboards, singing-arc speakers, and ingenious wave-shaping techniques that gave the Telharmonium its unique sound and musical identity will all be included. But other parts will use the latest technologies, materials, and engineering processes.

It will also implement ideas that Cahill wrote about but never got to implement. Ideas that might have gone into his own Mark IV.

Even with the patents and these clear goals, much is still open to interpretation. After reading so many pages of his words and ideas and fascinations, I feel like I know him. We share a vocation and would have understood each other perfectly. In fact, if he was alive today, we would probably be collaborating. So this project is my collaboration with Thaddeus Cahill.

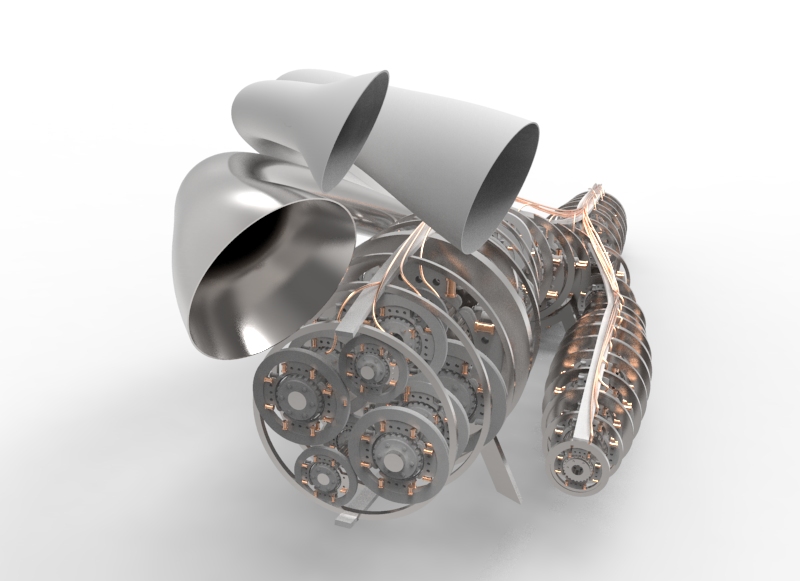

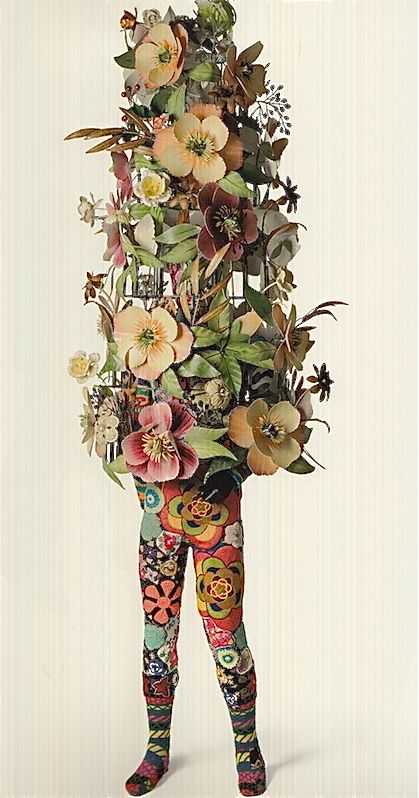

My design aesthetic for the Mark IV is equal parts big science, fine arts, and inexplicable delights. It will be smaller than the original but still of an impressive and architectural scale.

I'm currently developing a new design for the Mark IV. The images below represent a whimsical first pass that I've since abandoned. But the palette of materials and colors is likely to stay the same.

Below are some of the design inspirations for the Mark IV.

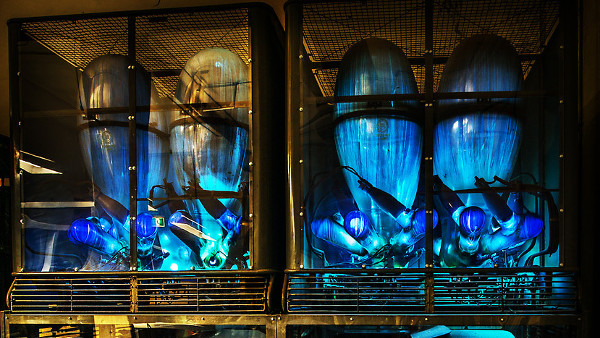

I'm very excited to appropriate one of the most beautiful artifacts of the early electric age — the mercury arc recitfier. Like a luminous creature from the blackest depths of the sea, these torso-sized vacuum tubes were invented in 1902 by Peter Cooper-Hewitt and may have been used to flatten out the DC electricity used by parts of the original Telharmonium.

Whoever brings this amazing, lost history back to light will own the whole story of birth of electronic music. And all of the media potential and business potential that comes with it.

This is a great subject for a documentary or a mini-series.

The unveiling of the instrument can be accompanied by performances from various electronic musicians. And with the release of recordings and videos.

Beyond that, its new life in the 21st Century may be as unbounded as the inventiveness and creativity of the people who use it to create music, events, media and anything else with it.